Cronache

2010: The third ikkyo: aikido between the lamas

Indice articoli

Ever since I was a very young boy I have been attracted by the incredible fascination and charm of Tibetan culture. To tell the truth, everything started when my sister, who was fully aware of my complete adversion to reading and wanted to do something about it - somehow, came up to me recommending a book which she assured I would find palatable.

Ever since I was a very young boy I have been attracted by the incredible fascination and charm of Tibetan culture. To tell the truth, everything started when my sister, who was fully aware of my complete adversion to reading and wanted to do something about it - somehow, came up to me recommending a book which she assured I would find palatable.

And she was right: that book came to me as an astonishing discovery. It was called The Third Eye, and was written by one Tuesday Lobsang Rampa – whom I later discovered to be a rather dubious and controversial figure.

The story, for those readers who've never heard of the book, is allegedly autobiographical, and relates the life of a boy who is brought up in a Tibetan monastery. If anything, it certainly paints an enjoyable and vivid picture of the atmosphere of the world it purports to describe – and captures that world at a time in which its purity had not been tainted by subsequent events.

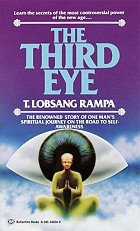

In the isolation of the Himalayan mountains, which sheltered it from outside influence, the medieval culture of Tibet miraculously had survived intact until 1959, preserving its perfect harmonisation with one of the most hostile natural environments in the world – a condition which went back through many centuries. 1959, however, was the year of the violent and illegitimate Chinese occupation of Tibet, and the survival of a magnificent civilization which for instance, keeping faith to the profecy of an ancient oracle, to this day even refuses to employ the wheel in transportation, was suddenly and seriously put into jeopardy. As a matter of fact, the only moving wheels in pre-Chinese Tibet were the prayer wheels which this outstandingly devout people unceasingly kept turning. It is for things like these that once one has come to be acquainted with the people of Tibet, one cannot fail but love them.

In the isolation of the Himalayan mountains, which sheltered it from outside influence, the medieval culture of Tibet miraculously had survived intact until 1959, preserving its perfect harmonisation with one of the most hostile natural environments in the world – a condition which went back through many centuries. 1959, however, was the year of the violent and illegitimate Chinese occupation of Tibet, and the survival of a magnificent civilization which for instance, keeping faith to the profecy of an ancient oracle, to this day even refuses to employ the wheel in transportation, was suddenly and seriously put into jeopardy. As a matter of fact, the only moving wheels in pre-Chinese Tibet were the prayer wheels which this outstandingly devout people unceasingly kept turning. It is for things like these that once one has come to be acquainted with the people of Tibet, one cannot fail but love them.

It is quite possible that I was simply rather impressionable as a teenager, and all too easily affected; but to this day, I still feel the emotional surge the book first brought to me, whenever I think back on my first reading it. I found myself thrown into a fable-like world of huge mountains and endless valleys; it made me perceive the esoteric atmospheres and holy darkness inside the monasteries. Thinking back upon it, I now realize the book fed into me the initial enthusiasm which later lead me to take certain significant steps in my life, and which still acts as a powerful motivator. It brought to me the curiosity to travel and meet other civilisations, the interest for the vast riches of oriental culture, and the search for an amazing martial art which would enable a sapling youth to measure up to adversaries stronger than himself.

It is possible that really is how it all started. At any rate, in 1985 I went on my first journey to the East – first stopping in Thailand, and then, via Hong Kong, over to China, just as it cautiously began to open its borders to tourists from the West. Being drawn as though by a powerful magnet, on 5 August 1985, at the end of a quest fraught with all kinds of logistic and (most of all) bureaucratic difficulties, I finally arrived in Lhasa, and thus realised a dream I at first had not dared hope could come true. That was my first encounter with the amazing civilisation that lives nested on the roof of the world.

I must say that even then, after twenty-six years, the effects of Chinese domination were already heavily conspicuous. The effects of the systematic destruction of monasteries, of (enforced) immigration from China and the importation of contemporary urban styles of life were everywhere to be seen.

I must say that even then, after twenty-six years, the effects of Chinese domination were already heavily conspicuous. The effects of the systematic destruction of monasteries, of (enforced) immigration from China and the importation of contemporary urban styles of life were everywhere to be seen.

The new settlements represented a wanton insult to local architecture and the discrete manner in which the Lhasa of old had been conceived.

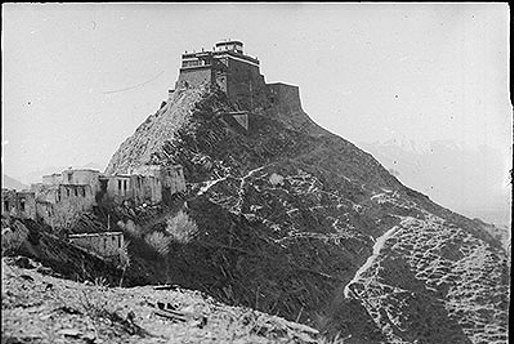

A city which had always been dominated by the imposing presence of the Potala (luckily spared by the iconoclastic fury of the Chinese).

Many were the signs of the wind of destruction that had swept over Tibet, and although the knowledge I then had of the local culture was extremely limited, the contrasts were oustanding and conveyed a most vivid sensation of all that had gone lost.

The effect of all of this on me (and likewise on the very scarce Western visitors there were) was a profound feeling of sadness, anger, and pity. I felt aggrieved, and the admiration for everything there was to see was curtailed by sadness.

The effect of all of this on me (and likewise on the very scarce Western visitors there were) was a profound feeling of sadness, anger, and pity. I felt aggrieved, and the admiration for everything there was to see was curtailed by sadness.

I remember the desolation and how my heart sank when, as I walked about Lhasa, trying to find my bearings and identify the sites I had read of in the book, I asked a local to show me the way to the Chak Pori – The temple of Tibetan medicine, the very place where the story is set.

I remember the desolation and how my heart sank when, as I walked about Lhasa, trying to find my bearings and identify the sites I had read of in the book, I asked a local to show me the way to the Chak Pori – The temple of Tibetan medicine, the very place where the story is set.

My gaze was directed to a hill which also appeared in the map inside my book. Only, at the top of the hill there was nothing left but a massive steel frame.

My gaze was directed to a hill which also appeared in the map inside my book. Only, at the top of the hill there was nothing left but a massive steel frame.

Nothing remained of that jewel of Tibetan architecture, of that vessel of infinite knowledge and wisdom except for a mount of grey rubble, a cascade of dust and debris along the sides of the hill.

Everything had been meticulously razed to the ground, brick for brick – and the same had been done to almost all the monasteries of the occupied territory. What a treasure the world had been deprived of!

In a certain sense, I was even unable to realise at the time how immensely privileged I was. There I was amongst those ruins, my mind consumed by the longing for a past that was irremediably lost, and not realising that things would actually soon change for the worse, rapidly and inexhorably. The accounts I have heard from people who visited Lhasa after me, even only a few years later, have completely obliterated any desire I might have had to go back. I suffered too greatly at the carnage the Chinese were deliberately making of Tibetan culture: transforming that remote province into a resource of wealth, pillaging its riches, exploiting it as a nuclear dump and tourist attraction, submitting it to unbeliavably asphixiating military patrols in order to prevent rebellion and grant their hold over what they regarded as a buffer between them and India, that undesirable colussus thay have for a neighbour.

And yet, in a sense, the manoeuvres of destruction were to no avail: Tibetan culture managed to survive and is as lively as ever. The providential escape of the Dalai Lama, which came just in time to save his life, and India's generous offer of asylum have ranted its perpetuation. Millions of Tibetans have since then crossed the Himalaya on foot to flee Chinese prevarication and violence. The exodus continues to this day, and the refugees who survive the desperate crossing of that ocean of ice that lies at over 15,000 feet of altitude are greeted both by the Indian government and by the community of Tibetans who have rebuilt a centre in which to perpetuate their cultural identity in the vicinity of the town of Dharamsala, in northern India.

And yet, in a sense, the manoeuvres of destruction were to no avail: Tibetan culture managed to survive and is as lively as ever. The providential escape of the Dalai Lama, which came just in time to save his life, and India's generous offer of asylum have ranted its perpetuation. Millions of Tibetans have since then crossed the Himalaya on foot to flee Chinese prevarication and violence. The exodus continues to this day, and the refugees who survive the desperate crossing of that ocean of ice that lies at over 15,000 feet of altitude are greeted both by the Indian government and by the community of Tibetans who have rebuilt a centre in which to perpetuate their cultural identity in the vicinity of the town of Dharamsala, in northern India.

My love of Tibetan culture later inspired me to become a member of the Italia-Tibet society and to embark on a journey to Laddak in 1986. In 1997 my wife and I joined a long distance adoption program; then, four years ago, we went to visit a large refugee colony in southern India, and finally were able to meet the Tibetan family and the child whose upbringing we had sponsored: she is now a rather shy teenager, but speaks far better English than I do.

So far, I would say we are in the bounds of ordinary, predictable events: when one feels attracted to a culture, it is only normal they should sooner or later come into more immediate personal contact with it. What I could not have foreseen in the slightest degree is what happened to me last year.

It is probably best if I give some background information first and explain that, in February 2004, a man called Roberto Rivola, and his partner Ivana enrolled at my Dojo: Roberto is a rather outstanding character; Ivana is his companion not only in life but in business also, and the reason they had come to the Dojo was their common interest in Aikido, the Japanese martial art I have practiced for many many years, and also teach.

It is probably best if I give some background information first and explain that, in February 2004, a man called Roberto Rivola, and his partner Ivana enrolled at my Dojo: Roberto is a rather outstanding character; Ivana is his companion not only in life but in business also, and the reason they had come to the Dojo was their common interest in Aikido, the Japanese martial art I have practiced for many many years, and also teach.

The line of business Roberto and Ivana are involved in a quite remarkable: they are illusionists and have a specialisation in escapology (same as the great Houdini, that is).

Roberto usually performs on cruise ships and has the stage name of Robert Kimera. Travelling the world over, he has developed a particularly open and cosmopolitan frame of mind. Alongside this, martial arts have been his passion from the age of eight.

His first contact with Aikido came very early on, under the guidance of Maurizio Pastore, a teacher very few people in Italy will be able remember, who at the time was living temporarily in Faenza, Roberto's home town.

His first contact with Aikido came very early on, under the guidance of Maurizio Pastore, a teacher very few people in Italy will be able remember, who at the time was living temporarily in Faenza, Roberto's home town.

Roberto assiduously, almost obsessively pursued the study of various styles of martial art and achieved a high level of mastery in each, with grades ranging from first to sixth Dan. First and foremost he devoted himself to Kick boxing, and has competed at international level; he also trained in Shotokan Karate, Nambudo, Ju Jutsu, Escrima, and also Wing Chung and several styles of Kung Fu and Thai Chi.

As often happens in the martial arts world, this long path eventually led Roberto back to Aikido. During a longer stay at his home in Cattolica, a town on the east coast of Italy not far from where I am, he again decided to take up Aikido practice. He thus came to my Dojo and was followed by Ivana, whose out of the ordinary aptitude became immediately apparent.

Due to the nature of his work, Roberto had difficulty setting a regular training routine. Worst of all, he was later prevented from training by the rather serious consequences of a banal accident that occurred while he was preparing for a sensational performance: a free fall parachute jump whilst tied up in a straitjacket.

The accident and the prolonged period of rehabilitation meant that he was forced to take a long leave from the martial arts, during which time Roberto continued to cultivate his passion for the culture and religions of the East, and practiced meditation and Yoga. Eventually, his spiritual search and interest in Buddhism inspired him to make the decision to move to India and live at the Palpung Sherabling monastery, where he's now been living for three years together with Ivana.

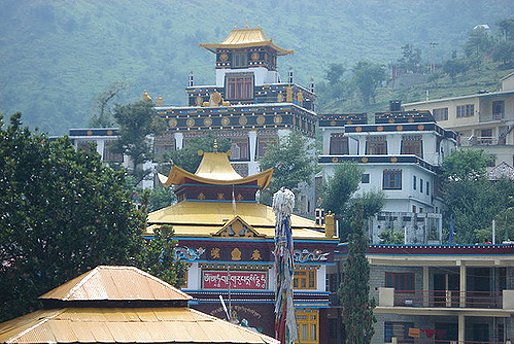

This monastery, cast amidst mountain scenery and immersed in woodland, is situated at about thirty miles from the residence of the Dalai Lama – which is not, as is often said, in Dharamsala, but in the same area as this monastery, at McLeod Ganj, more precisely.

This monastery, cast amidst mountain scenery and immersed in woodland, is situated at about thirty miles from the residence of the Dalai Lama – which is not, as is often said, in Dharamsala, but in the same area as this monastery, at McLeod Ganj, more precisely.

In the fifty years of the Dalai Lama's permanence here, what was formerly an ordinary village in the mountains has become a kind of Mecca for anyone with an interest in Buddhism. It has also become a popular destination with tourists in search of alternative destinations, so that it now gathers a lively and colourful miscellany of young travellers distinguished by their extravagant attires and temperament.

In the three years of their stay at the monastery, Roberto and Ivana have harmonised more and more fully with its life patterns. Their teachers are the two leading figures of Tibetan Buddhism after the Dalai Lama, namely His Holiness Gyalwa Karmapa and Kenting Tai Situ Rimpoche.

Let me add a few words, just so that the calibre of these figures, whose audiences we were fortunate enough to attend, might be understood: the former is designated to take the place of the Dalai Lama and to be the one to recognise the Dalai Lama's future reincarnation, whereas the Tai Situ, who is regent abbot at the Sherabling monastery, will most likely be the one to teach him.

Let me add a few words, just so that the calibre of these figures, whose audiences we were fortunate enough to attend, might be understood: the former is designated to take the place of the Dalai Lama and to be the one to recognise the Dalai Lama's future reincarnation, whereas the Tai Situ, who is regent abbot at the Sherabling monastery, will most likely be the one to teach him.

The term Rimpoche, which literally means "precious", is the designation which in Tibetan Buddhism is reserved for the religious figures whose former incarnation is known with certainty.

With Karmapa, the chain of former incarnatons leads back to Prince Siddharta, the very Siddharta who became the Buddha when he reached enlightenment and initiated the circulation of his doctrine throughout Asia.

But I realise I have been wittering on for some time now, and not yet accounted for the occurrence of the facts that the photos you see make perfectly plain.

But I realise I have been wittering on for some time now, and not yet accounted for the occurrence of the facts that the photos you see make perfectly plain.

I mean to say, I have not yet explained how it came to pass that I, who am not an eminently meditative aikidoka, should end up in a monastery – not to be initiated to meditation, but to teach the monks my aikido!

The fact is that as Roberto became ever more integrated with life at the monastery, and in parallel became desirous usefully to contribute to its community; he thus ended up running a martial arts course with the benediction of the Tai Situ himself. Details of this course, which embraces a wide range of disciplines and really is the expression of the many facets of Roberto's expertise, are to be found at the website he created especially to divulge this experience.

The fact is that as Roberto became ever more integrated with life at the monastery, and in parallel became desirous usefully to contribute to its community; he thus ended up running a martial arts course with the benediction of the Tai Situ himself. Details of this course, which embraces a wide range of disciplines and really is the expression of the many facets of Roberto's expertise, are to be found at the website he created especially to divulge this experience.

Roberto is, among other things, a qualified Physical Education teacher. When he was first entrusted with a group of twenty young monks his course was a great success, so that this year his course was reconfirmed – with twice the number of pupils.

During their last stay in Italy, Roberto and Ivana made a stop at my Dojo to tell us of this extraordinary adventure and of the project they're working on. In the end they came up with a suggestion I welcomed, but was yet rather difficult to take up.

India is not exactly round the corner, nor is Tibetan culture the only one to arouse my interest: I'm interested in all cultures, in fact, and my destination for this year were supposed to be the arid landscapes of the Rajastan desert. It so happened, however, that my friend Claudio Cardelli, an expert student of Indian and Tibetan culture, with thirty-three journey to those regions behind him, informed me as I was about to set off of the torrid heat-wave that was then sweeping across India – with over 40° Celsius in Dheli and over 50° in Rajastan! Hardened travellers we are, but not masochistic. So that is how, with a last minute decision, we decided to head northward to the cool of the mountains and go on a trekking trail that would take us to an altitude of 12,000 feet. Having made the latter decision, there was no excuse not to pay our friends a visit: we thus hastily stuffed a keikogi and hakama into our backpacks and off we went.

As soon as we reached our destination we had our first stroke of luck: upon arrival at the Palpung Sherabling monastery I enquired after Roberto and Ivana and was guided to a hall full of people where Tai Situ was to hold an audience – the last one before going on a long retreat which was to start only two days later.

As soon as we reached our destination we had our first stroke of luck: upon arrival at the Palpung Sherabling monastery I enquired after Roberto and Ivana and was guided to a hall full of people where Tai Situ was to hold an audience – the last one before going on a long retreat which was to start only two days later.

The audience has just begun and my two friends are indeed the first to be received by Tai Situ in the room reserved for the consultation. Being members of the monastery, they were able to make it so they were the first to be allowed inside. I have to wait a long time – everything in India takes time – and watch closely the various delegations of the faithful who've arrived from all over the world.

The largest delegation comes from Hong Kong: they wear t-shirts of the same deep-red as the monks' robes, with chinese characters printed on them, and as a gift to the monastery they bear a sculpted jade dragon wrapped up in a kata, the ritual white scarf used in Tibet.

There are groups of western dames with that air about them of the English Romantic gentlewoman; numerous people with the features of the Indian subcontinent, most of whom are clearly Tibetan. I bide my time in conversation with a peculiar youth – born of Austrian father and English mother, and living in Mongolia! He's looking totally spaced, his eyelids heavy and drooping, and generally gives me the notion his search of a higher plane involves not only meditation, but also a set of shortcuts.

There are groups of western dames with that air about them of the English Romantic gentlewoman; numerous people with the features of the Indian subcontinent, most of whom are clearly Tibetan. I bide my time in conversation with a peculiar youth – born of Austrian father and English mother, and living in Mongolia! He's looking totally spaced, his eyelids heavy and drooping, and generally gives me the notion his search of a higher plane involves not only meditation, but also a set of shortcuts.

Our friend are out at long last, and it brings us great joy to see each other in such a special place and so many miles from home. Roberto explains that the opportunity really is not to be missed, so we persist in the long queue and finally are admitted to a brief audience with the Tai Situ – a figure whose standing in that culture might be compared to what the Pope is to a Catholic. Roberto introduces me as his Aikido teacher, and suggests that for a few days I be entrusted with the pupils who attend his habitual three-hour classes. The simplicity and cordiality of the Tai Situ impress me greatly, and bring back to me the complex of emotions I felt upon meeting the Aikido Doshu face to face at the Tokyo Hombu Dojo.

This utter simplicity of behaviour, and the capacity to make the highness of their rank not burdensome to their interlocutor must be a prorogative of the truly great: it is the very simplicity of the exchange that made it a magical and intensely stirring occasion. Having had the Kata placed around my neck as a blessing and salute, I take my leave in a state of mild confusion. Is it true, then? I shall be teaching at the dojo in the monastery on the morrow! We are then accompanied to our rooms at the recently built monastery guest house, and immediately set out on an exploration of its buildings. The most impressive space is the ample covered court fronting the temple.

All along the other three sides of the court are the monks' lodgings and study rooms, and the physical space of the court acts as resonator to the chants the monks intone, resonating constantly in the varied registers of the monks – from the high pitches of the very young to the incredible bass notes of the elders.

All along the other three sides of the court are the monks' lodgings and study rooms, and the physical space of the court acts as resonator to the chants the monks intone, resonating constantly in the varied registers of the monks – from the high pitches of the very young to the incredible bass notes of the elders.

Drums, bell, the deep lowing of the long horn instruments which announce the start of a function, the incessant to and fro of monks clad in red and yellow... the place really seems to stand outside reality.

We've come to the following day: at three thirty in the afternoon the beginners' class, which has run for just a few months, is supposed to begin, but for the occasion the two courses will merge and we shall all do Aikido together for three hours.

We've come to the following day: at three thirty in the afternoon the beginners' class, which has run for just a few months, is supposed to begin, but for the occasion the two courses will merge and we shall all do Aikido together for three hours.

At the dojo, which has been accommodated within an internal courtyard sheltered by a light covering, I find the younger pupils already there, bent over the tatami and intent on cleaning it with the handle-less brooms that are typical of India.

Roberto introduces me to the students, and the effect of having before them the teacher of their own teacher is obviously exciting to these young men, charged with enthusiasm like sticks of dynamite.

Their only possessions often are the clothes they wear; several of them were orphaned, and ignore where they were born; communication amongst them can sometimes be a struggle, because they speak the dialects of the remotest and most varied provinces of what once was the ancient and vast kingdom of Tibet.

Their only possessions often are the clothes they wear; several of them were orphaned, and ignore where they were born; communication amongst them can sometimes be a struggle, because they speak the dialects of the remotest and most varied provinces of what once was the ancient and vast kingdom of Tibet.

The young monks study hard and are tempered by the austere style of living at the monastery, to which many of them were not brought by vocation. As it turns out, not even participation to this course was decided by them, but by their teachers.

They're pure as crystals, and have light shining through their eyes; on this day, an opportunity has been opened to them that in their view is extraordinary. All of this is manifest without any words being spoken.

As soon as Roberto gets them started on their habitual "free-form warm-up", my jaw drops in amazement: what actually begins is a whirlwind of acrobatics of so extreme a degree of spontaneity and daringness we might as well call it sheer recklessness.

As soon as Roberto gets them started on their habitual "free-form warm-up", my jaw drops in amazement: what actually begins is a whirlwind of acrobatics of so extreme a degree of spontaneity and daringness we might as well call it sheer recklessness.

I'm astounded by wild stretching exercises I see: in one of them one youth is tugged and pulled at from both sides by two companions, and seemingly must only do his utmost to survive the drawing and quartering.

One of them initiates a leapfrog merry-go-round as expiation for the punishment Roberto had inflicted the previous day, and thus not miss the first part of my lesson.

Comparing the live wire energy of these pupils to the dull apathy of our youths, reared on snacks and play stations, I also soon end up feeling galvanised by a peculiar enthusiasm I had never felt before.

Comparing the live wire energy of these pupils to the dull apathy of our youths, reared on snacks and play stations, I also soon end up feeling galvanised by a peculiar enthusiasm I had never felt before.

Without going into a chronicle of the actual training session, I shall simply say that their concentration and enthusiasm, their playful and vibrant energy made it so that my habitual didactic approach and manner of explaining produced incredible results.

Without going into a chronicle of the actual training session, I shall simply say that their concentration and enthusiasm, their playful and vibrant energy made it so that my habitual didactic approach and manner of explaining produced incredible results.

Notwithstanding the great obstacle of not being able to explain myself in words, but only by gestures, this prodigious array of athletes was unbelievably quick at taking in every movement I proposed, and every correction I made.

By the end of the lesson, I was by far the one who'd had the greatest fun.

As if we hadn't had enough already, all of a sudden an out of breath messenger arrives delivering a message in hurried wispers: the Tai Situ himself, accompanied by a contingent of solemn elders of the monastery, will be honouring us with his visit! A deep, unreal silence breaks up the young monks' joyous banter, giving turn to an attitude of utter respect and devotion.

Having heard the report of my most favourable impression of the qualities I'd been able to observe at work with these pupils, as also of the groundwork Roberto had done, the Tai Situ suddenly relaxed into an informal, almost playful attitude. Similar behaviour came completely unexpected from a man of such rank, and was especially surprising to the young monks.

Having heard the report of my most favourable impression of the qualities I'd been able to observe at work with these pupils, as also of the groundwork Roberto had done, the Tai Situ suddenly relaxed into an informal, almost playful attitude. Similar behaviour came completely unexpected from a man of such rank, and was especially surprising to the young monks.

What we then witnessed in sheer amazement, was a performance by the Lama, who initiated with Roberto an exchange of martial techniques – he too being a dedicated student of the martial arts.

That first lesson was thus followed by another four, to the mutual and growing satisfaction of all involved.

Their almost shameless aptitude to learning was almost provocation to me. As I came up with movements and situations of greater complexity, they would take the challenge as a stimulus, and with great curiosity, and a manifest desire to gratify me.

Their almost shameless aptitude to learning was almost provocation to me. As I came up with movements and situations of greater complexity, they would take the challenge as a stimulus, and with great curiosity, and a manifest desire to gratify me.

I mean – in the five days I was there I was able to go through the full Aikido 'syllabus' down to koshinage from all kinds of attack situations, ushirowaza included.

On the last day I was thus well curious to put to the test the progress we had made.

On the last day I was thus well curious to put to the test the progress we had made.

I thus ran an informal exam session on 6th kyu techniques and saw that fourteen of twenty in the advanced class would have passed.

Not my merit, certainly. The merit, rather, goes to the commendable foundation work laid down by Roberto, who is only an Aikido 5th kyu, and to the extraordinary talent of his pupils; quite possibly, it all came out of the imponderble, magical concord that quite spontaneously set in among them.

As a farewell, I gave each of them my visiting card, with the details of my dojo and of the dojo's website. Although it is only sporadically, the youths are allowed to use a computer so as to keep touch with the outside world: that very simple paper card and address were a real gift to them.

Proof of this came in the evening, when we were seated with our friends inside the plain tavern of the monastery and were joined there by Damchoe Thinley, who throughout had translated into Tibetan my very rudimentary English, and who, aged almost thirty (in Tibet the count begins from the time of conception) is the most mature of the young disciples. He bore a gift for me.

First he placed a pure white kata around my neck, then presented me with a book which contained reproductions of the Tai Situ's artwork, calligraphies, paintings, and photographs, which they had managed to buy by pooling together their meagre finances – their personal wealth really amounting to a few farthings. I was deeply moved. We shook hands and embraced by way of farewell – and who knows that this adventure might not have some kind of a sequel.

What has compelled me to write this article is the strong emotional charge I experienced and the indelible mark it impressed on me. Whatever may occur next, the fact is that something entirely special has taken place.

What has compelled me to write this article is the strong emotional charge I experienced and the indelible mark it impressed on me. Whatever may occur next, the fact is that something entirely special has taken place.

In the course of this exchange, I was able to combine my deep affection for the culture of Tibet with my passion and expertise in Aikido: as a teaching experience, it was unlike any I have had.

It is one thing to teach at your own dojo, to your pupils, or to convey technical skills to the people who pay a fee to join my seminars.

Here the exchange was on an even footing, pleasure for pleasure, learning satisfaction for teaching satisfaction, and all in the awareness that I was able to give something to these young men who, in spite of what we might also see as unfortunate circumstances, are still able to send out an incredible wave of optimism and positive energy.

That group of young monks really did touch my heart, and the great distance is the only real obstacle there is between us. But then, we all know how enthusiasm can lend us wings.

That group of young monks really did touch my heart, and the great distance is the only real obstacle there is between us. But then, we all know how enthusiasm can lend us wings.

Montevecchi Ugo

Note:

Roberto Rivola published a book in 2008 on the question of Tibet and the violence perpetrated against this people. The title of the book is "Verità nascoste"; it was published at the author's expense and all proceeds goes a contribution to the Tibetan cause. The book may soon be re-edited by the publisher "Il Cerchio".